PRINTING – LEAVING TRACES

DÓRA MAURER’S GRAPHIC OEUVRE

1955-1980

Printmaking, as an aspect of Dóra Maurer’s oeuvre, has brought forth visual notions that have influenced her entire life’s work. Furthermore, as a result of its unique quality and experiential nature, her body of graphic works also constitutes a defining chapter in the history of Hungarian printmaking. Maurer completed her studies in 1961 in the Graphic Arts Program of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. After 1960, she enriched her prints through technical experimentations. Around 1970, a significant turn occurred in her work as a graphic artist: rather than continuing to focus on depictions etched onto the plate, she turned her attention towards printing – leaving traces – itself as a process and action, and towards printing as documentation. She has pursued this train of thought in the Hungarian art of the period with unparalleled consistency, extending and translating the problematic of leaving traces and making marks to such cognate media as photography, motion picture and painting. During this period, which lasted approximately until 1981, she laid the foundations for the conceptual direction in Hungarian printmaking. In spite of the fact that, in 1961, her experimental copper engraving series was not accepted as her diploma work, her career is closely tied to the Academy nevertheless: following her practical training in art pedagogy, in 1990, she began to teach at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. As of 2008, she has born the title of “Professor emerita”.

For Dóra Maurer, choosing intaglio printing was not so much a technical decision, as it was the core thought – the conceptual seed – for creating artwork. Her oeuvre, which spans over half a century, is characterized by a rich toolset of artistic expressions which, in addition to traditional graphic and painting techniques and approaches, also include photography, motion picture and action art. Furthermore, in her graphic works, she explores questions which, extending over these various media, constitute the fundamental problematics of her entire life’s work. These include leaving traces as a method of elemental image making, the image as document of an action process, the predictable and unpredictable movements of visual components, the reversible and irreversible structure of image sequences, the relationship between the original and its copy, as well as the interactions between rules and random chance. A portion of these visual notions originated from her practical experiences in printmaking, only to then unfold expressly through this medium and later continue through other technical means of expression. For Maurer, the unique process, materiality and philosophy of creating graphic artwork are aspects not of a self-directed speciality, but of a

phenomenon that allows insight into the internal dynamics of the relationship between reality and creating art.

Student years

Dóra Maurer began her studies at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in the academic year 1955/1956, immediately following her graduation from the High School of Fine Arts. In the Academy’s Graphic Program, she studied under the tutoriage of Gyula Hincz and Sándor Ék. She became familiar with the technique of copper engraving in the autumn of 1956; intaglio printing remained a defining element of her entire graphic oeuvre. While she felt at home in creating the kind of tonal drawings that were in line with official expectations, she was much more strongly influenced by the art of István Nagy, József Nemes-Lampért, Jenő Barcsay and Lajos Kassák, than she was by academic realism. Her sensitively contoured profiles, modelled after friends, were created in the spirit of Picasso’s classicizing line drawings. It was János Major, a fellow student one year ahead of Maurer, who introduced her to the experimental forms of copper engraving. In her third year at the Academy, in reaction to her novel technique and expressive realism, there was talk of her possible expulsion. Starting in 1959, influenced by 15th and 16th century Dutch realism and the German expressionism of the 1920s, she moved increasingly away from the idealizing viewpoint of socialist realism. Her identically titled, copper engraved rendition of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Dulle Griet / Mad Meg is a typical example of her ironic rewriting of the official “worker” thematic. Her alternative realism was summed up in her copper engraving series entitled Workers’ Movement Triptych, which was created for the anniversary of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The multi-figured, complex compositions represent the three phases of the rebellion: conspiracy, rebellion and retaliation, then starting over. In the first scene, the figures conspiring around the table were modelled after academy staff as well as Maurer’s friends and fellow students – from left to right: György Nagy, Miklós Melocco, Vera Vásárhelyi, a cleaning lady, János Major, a professional model, the furnace operator, Klára Deák and György Urbán. Some of these individuals can also be found among plotting figures in the scene that takes place after the revolution is crushed.

In spite of their apparent thematic conformation, Maurer’s copper engravings were far removed from the officially dictated orientation of academic education. In terms of her artistic outlook, she felt a kinship with representatives of the surnaturalism that was emerging at the time: László Lakner and his circle. Her diploma work entitled Everyday, completed in 1961, was an eight-piece copper engraving series which offered a subjective, lyrical panorama of her own present. She clearly broke away from the style of copper engraving that was dominant in Hungary, keeping an equal distance between the sculpturally shaped, classicizing realism of István Szőnyi’s followers and the pathos-strewn archaization of Kondor’s circle. In her prints, instead of flexible line drawings, Maurer created unique surfaces by etching (using etchants of various strength as well as the technique of “flat etching”) and printing with foreign materials (primarily textiles with various weaving patterns). In spite of her outstanding technical competence, her copper engraving series did not earn her a diploma. While her technical knowledge and skill were acknowledged by her teachers, according to the ministry representative who vetoed her work, “it [was] not appropriate to agree with this perspective.”

Psychic realism

Beginning in the early sixties, Maurer turned from the expressive realism and surnaturalism that defined her years at the Academy toward content that was surreal, magical, and imaginary. She became interested in transferring spectacles of nature – in all their microscopic flutterings and surreal formations – onto the plate. The alternating impulses of subjective observation, free association and philosophic abstraction set the tone of two significant graphic series from the early eighties: Pompeii Cycle and Evening Scenes.

When, in 1963, she first received her passport, she took advantage of the fact that it allowed for longer stays abroad and spent months travelling through Italy and Greece. After returning home, she processed her experiences through two large-scale copper engraving series. Rather than depicting concrete landscape or cityscapes, the scenes of these engravings are explorations of the relationship between a wanderer on her own spiritual journey and the accumulated layers of time. Instead of depicting antique ruins or historical events, the sheets of the Pompeii Cycle capture the poignantly beautiful experience of the circle of life and death, as it moves the traveller. She, like Piranesi, was also fascinated by the abundantly prolific energy of nature as it swallows monumental architectural structures – the melancholy of disintegration. The 11 sheets of the Evening Scenes series were created in parallel with the Pompeii Cycle. Its images were similarly inspired by the artist’s travels in Italy and Greece, albeit in a less concrete manner. The supple, dissolving forms of Evening Scenes capture moods; they are visions of internal – rather than external – landscapes, venturing into the realm of the unconscious.

For creating the biomorphic formations that appear in her prints, instead of using the copper engraving as a carrier of line drawing, she utilized its surfaces – formed with various materials and etching processes – to superimpose layers of various textures in a montage-like fashion. The unique richness of the resulting surfaces are a result of her own inventiveness and a series of systematic experimentations. In her view, copper engraving is an experimental medium, whose technical conventions can continuously be overwritten. During this period, her experiments centred on working the copper plate (and, thus, the print) in a facturally rich manner.

After finishing her studies, she insured her artistic freedom by creating compositions commissioned by the Képcsarnok Vállalat (“Gallery Company’). Between 1961 and 1968, Maurer created nearly forty compositions, primarily consisting of depictions of factories and historical scenes. These works continued in the vein of the expressive-magical realism that she had developed during her years at the Academy, in terms of their strong-featured, intensely-gestured portrayals, as well as their richly textured engraved, etched surfaces (Eviction of the Brennberg Miners, Sallai Is Arrested).

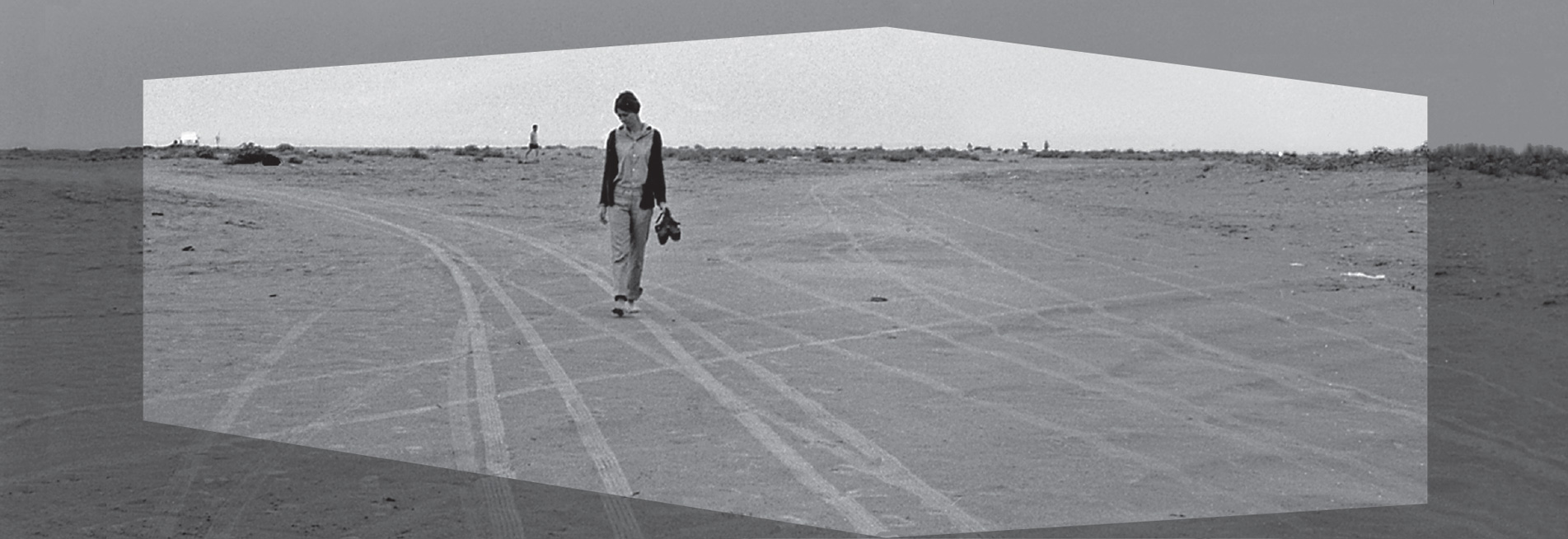

Action graphics

From 1970, Maurer systematically broke away from previous techniques of virtuosic image creation and began to regard the metal plate not as the image carrier but as a surface that documents the action of mark making. In a radical demonstration of this turn, she dropped the aluminium plate from a multi-storey residential building and then used it, damaged as it was by the impact, to create her print. In the case of Throwing the Plate from Very High, the print is a document of the impact of the plate hitting the ground. The cause of this effect was not a chemical reaction, but a direct action by the artist. In her “pedotypes”, the most ancient tool of mark making – the foot print – becomes an element of image creation. The action graphics created in and after 1971, which centre on the processual nature of printing, shows the subsequent phases of the effects that befall the plate (Trace of Movement). The composition entitled Accumulation documents the printing plate’s “slow process of forgetting”, as it retains the gradual fading and rearrangement of letters placed under it. The pages of Word Traces also follow the same principle, where the letters of a word are printed onto one another. The accumulation of letters overwriting one another extinguish – rather than enhance – the meaning of the whole. In her series created together with poet Bujdosó Alpár (Wortspuren), it is once again the bulge of the cardboard letters placed under the plate that emerge, but this time complete words disappear and take shape again. The text itself also refers to the disappearance of thoughts and works of art – their becoming invisible.

The age-old technique of frottage forms the basis of the work entitled Hidden Structures. These works are even more intensely permeated with the previously experienced dynamic of concealment and revelation, annihilation and restoration.

The work entitled Print till You Drop consists of subsequent prints created by a single aluminium plate on which lines have been drawn vertically, using a drypoint needle – thereby documenting how the print changes with the gradual wear of the plate and the increased flattening of the grooves carved out by the etching needle. The changing printed image captures an essential element of the process of printmaking itself: the presence of the variable in repeating images. With the symbolic power of surfaces turning from dark to light, from heavy to slight, it demonstrates that – in case of the traditional techniques of graphic art – no two prints created with the same carrier are ever identical. The ordered row of same-size plates and the distance between grooves, increasing in accordance with the Fibonacci sequence, provide the solid framework within which the unpredictable process of continuous fading takes place. The fading of the lines also expresses the physical exhaustion of the artist engaged in the actual act of printing – symbolic impermanence, transformation from the material into the ethereal.

Curator: RÉVÉSZ Emese

Co-ordination: MAJSAI Réka

Graphic design: CZEIZEL Balázs

Exhibition PR: CSEJDY Réka

Texts: RÉVÉSZ Emese

Translations: RUDNAY Zsófia

Preparatory work for the exhibition:

BÓDI Kinga, FÜSPÖK Zoltán, IZINGER Katalin, PANKASZI István, PŐCZE Attila, TARR Hajnalka

Exhibition installation:

BÁLVÁNYOS Levente, GYŐRI István

The Hungarian University of Fine Arts would like to thank the private individuals and the following institutions for lending works of art to be displayed at the exhibition.

Hatvany Lajos Múzeum, Hatvan

Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum, Budapest

Szent István Király Múzeum, Székesfehérvár

Szépművészeti Múzeum – Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, Budapest

SUPPORTED BY

National Cultural Fund of Hungary,

Gályor-Maurer SUMUS Foundation