BEFORE REVOLUTION

The Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts between 1945 and 1956

- INTRODUCTION

- CREDITS LIST

- CHRONOLOGY

- STUDENTS IN THE CIRCLES OF THE EUROPEAN SCHOOL

- MASTERS IN CHANGING TIMES

- THE ACADEMY IN THE FIFTIES

- PUBLIC DIPLOMA DEFENCE PRESENTATIONS

- THE AESTHETICS OF A NEW ACADEMISM

- FROM SHADOW INTO LIGHT ̶ GRAPHIC ART EDUCATION IN THE FIFTIES

- 1956 ̶ IMAGES OF REMEMBERING

The storms of history that raged in Hungary between 1945 and 1956 also left their mark on the stronghold of the country’s art education – the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. The exhibition entitled Before Revolution focuses on the period of the Academy’s history between World War II and 1956 Revolution. The distinct segments within this timeframe signify some years of hopefulness and temporary opening between 1945 and 1948, and, then, the solidification of the State-Party system – which had been established based on the Soviet model – to be concluded with the Revolution of 1956.

The first section of our exhibition offers a glimpse at the artistic experimentations of the post-war years. Those who began their studies at the Academy of Fine Arts around 1945 could still freely experiment with cubism, expressionism or abstraction. Such free and progressive endeavours found a home within the circles of the European School. In the beginning, the Academy neither encouraged nor hindered its students’ progressive pursuits. Géza Fónyi’s mosaic class and Jenő Barcsay’s glass painting class offered shelter to young art students seeking decorative formal solutions, even while realistic tendencies were growing stronger. The nonfigurative, expressive and surrealist ambitions, which were still vibrantly present in student circles at the time, are represented in the current exhibition by the works of Ferenc Jánossy, György Hegyi, Zoltán Nuridsány, Gellért Orosz and András Rác.

The second unit of the exhibition invokes the figures of the master teachers who taught at the Academy during this period. By 1950, the faculty had been replaced completely: with the exception of István Szőnyi and Zsigmond Kisfaludi Strobl, no one remained from those who had taught under the previous regime. The core of the newly formed faculty consisted of artists from what was formerly known as the Gresham Circle (Aurél Bernáth, István Szőnyi, Pál Pátzay), accompanied by avantgarde artist from the 1910s, who were of a leftist persuasion (Róbert Berény, Sándor Bortnyik, János Kmetty and Bertalan Pór). In spite of the strong political pressure on the school, the majority of these excellent educators submitted to the mandatory doctrine of socialist realism only partially and on paper. All efforts by bureaucratic decision makers to conform art to certain schemes and dogmas were in vain: the artistic excellence of these teachers, along with their awareness of the European art scene, allowed them to rise above these constraints and provide their students with a high standard of artistic education.

This atmosphere of fresh and free exploration was radically changed by the introduction of the 1949 educational reforms. The new academism, which unfolded during the fifties, comprises the central element of this exhibition. With the appointment of Sándor Bortnyik as director, centralized, conservative art education became the dominant approach at the Academy. The essence of the reform, which had been formulated based on the Soviet model, was in reinstituting 19th century academic methods. This approach was grounded in a strict regulation and constant control of education, which reduced the personal freedom of both teachers and students to a minimum. As a first step of this disciplined and uniformed perspective, students were required to copy plaster models, which was then followed by life drawing studies, aimed at creating a visual representation – in the dry-drawing style – of what was seen in all its material detail. The purpose of this approach was to lay the groundwork for

CREDITS LIST

The Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts between 1945 and 1956

Hungarian University of Fine Arts (Barcsay Terem, Aula)

Curated by: Katalin B. Majkó, Emese Révész

Scenography: Judit Csanádi, Anka Józsa

Graphic design: MMSZK Kötöde ‒ Tamás Hoffmann, Réka Imre, Ivett Lénárt, Dániel Máté & Ádám Albert

Communication: Réka Csejdy

Preparatory work for the exhibition: Anikó Bojtos, Réka Majsai, Attila Rum, György Sümegi, György Szücs, Tibor Wehner

Conservation of the exhibited work: Veronika Szalay, Krisztián Kovács, Péter Menráth, Mátyás Horváth, Erika Szokán, Zoltán Füspök, Csilla Szabó

The exhibition was set up by: Zsolt Berta, Zoltán Füspök, István Győri, Gyula Lakatos, Csilla Szabó, László Vásárhelyi Nagy

The Hungarian University of Fine Arts would like to thank the following institutions and private individuals for lending works of art to be displayed at the exhibition:

Herman Ottó Múzeum, Miskolc

KOGART, Budapest

Körmendi Galéria, Budapest

Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, Budapest

Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum, Budapest

Szegedi Tudományegyetem, Szülészeti és Nőgyógyászati Klinika

Thorma János Múzeum, Kiskunhalas

Szépművészeti Múzeum – Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, Budapest

former students and teachers of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts, as well as their descendants

www.mke.hu/forradalom_elott

On view:

21 October – 4 December 2016

Open daily from 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

1062 Budapest, Andrássy út 69.

The event is supported by the Memorial Committee established on the 60th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

Media support: ARTMAGAZIN

Additional support: NKA

CHRONOLOGY 1944‒1957

1944/1945

As of 29 October 1944, teaching was suspended because of the war.

On 9 April 1945, teaching resumed.

Make-up entrance examinations were held for those who had previously been rejected on account of their ethnic origin or other reasons, as well as for those who had just returned from captivity. The faculty at this time was comprised of Nándor Lajos Varga (rector), Rezső Burghardt, Béla Kontuly, István Boldizsár, Gedeon Gerlóczy, Emil Krocsák, István Szőnyi, László Kandó, Zsigmond Kisfaludi Strobl, Jenő Elekfy, István Kákonyi. Gyula Rudnay and Jenő Bory were sent into retirement. The teaching post for Life Drawing was filled by Aurél Bernáth, while Sculpture was now taught by Pál Pátzay and Béni Ferenczy. In Dezső Pilch’s absence, teaching responsibilities for the subject of Anatomy were assumed by Jenő Barcsay. Applied Art was taught by Endre Domanovszky. In July, László Kandó was elected rector by the Academic Council.

1945/1946

A curriculum reform was introduced, which nevertheless carried on the basic principle of the Lyka reform: naturalistic art education. The admission limit was doubled: the number of students who could be enrolled was raised to one hundred. The number of life drawing classes was increased from six to eight, with János Kmetty and Róbert Berény now on board as teachers. Literature was taught by László Cs. Szabó. Instruction of Applied Art and Mosaic Design was entrusted to Géza Fónyi. Justificatory Committees were formed, whose task was to examine the political trustworthiness of those returning from war prison camps as well as employees who had already been working at the Academy prior to the war. The management of the school announced its interest in the vacant spaces of the former Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest.

1946/1947

István Boldizsár and Rezső Burghardt were removed from their teaching posts as they had been deemed politically untrustworthy and put on the “B List”. The spaces of the former Műcsarnok were acquired by the Academy for its painting classes. Summer artist colony workshops were held in Veszprém, Zebegény, Szentendre and Miskolc. At the end of the academic year, Pál Pátzay was elected as the next rector.

1947/1948

Ferenc Sidló retired, his position was filled by András Beck. Aurél Bernáth received the Kossuth Prize.

1948/1949

The Academy launched its evening school for workers, led by Endre Domanovszky. Teachers of subjects in the humanities – Menyhért Takács, László Cs. Szabó, Gedeon Gerlóczy and Béla Ujváry – were relieved of their posts. The remaining members of faculty – Dezső Pécsi Pilch and Nándor Lajos Varga – were sent into retirement and replaced by László Bence and Bertalan Pór as teachers of Life Drawing. Teaching positions for the subjects of Art History, History of Architecture, Conservation, and Graphic Art were filled by Máriusz Rabinovszky, Virgil Borbíró, Nándor Kapos, and Károly Koffán, respectively. Géza Fónyi and his students created the mosaic on the floor of the Academy’s entrance.

1949/1950 – Year of the educational turn

Sándor Bortnyik was appointed director of the Academy. Béni Ferenczy and Jenő Elekfy were relieved of their positions. New teachers were employed within the Graphics Faculty (Sándor Ék, Gyula Hincz, György Konecsni, György Kádár), as well as for instructing Life Drawing (Gyula Pap, Béla Bán) and Sculpture (Sándor Mikus). The introduction of the New Organizational Policy and Curricular Scheme, radically changed the structure and principles of academic training. As an offering on behalf of both the students and their teachers, artworks were created in celebration of Stalin’s birthday.

1950/1951

The rules that regulated the everyday operations of education were made stricter. A number of disciplinary proceedings were initiated against students. Factory fieldtrips and “cadre recruitment” trips were organized to the country side. Marxism and Russian became a mandatory subjects. Party Secretary Zoltán Rozsnyai was appointed as a teacher of the Russian language. The first public diploma defence presentation was held. Summer artist colony workshops were organized in Sztálinváros and Miskolc.

1951/1952

The First Ideological Conference was held at the Academy. Led by the Registrar’s Office, students of the Academy visited an exhibition organized in honour of Mátyás Rákosi’s birthday at the Museum of the Hungarian Labour Movement. Mátyás Rákosi viewed the Academy’s end-of-year exhibition.

1952/1953

Róbert Berény was sent into retirement. Máriusz Rabinovszky died. Stalin died. The members of the faculty jointly observed the work of the Petőfi Farmer’s Cooperative in Páty. Summer artist colony workshops were organized in Tatabánya, Karcag, and Sztálinváros.

1953/1954

Róbert Berény died. Disciplinary proceedings were initiated against Viola Berki. Lajos Végvári was appointed head of the Art History Department. Because of what had been said at the Soviet Conference, disciplinary proceedings were initiated against István Bencsik, József Ircsik and László Patay. Jenő Barcsay was awarded the Kossuth Prize for his Anatomy for the Artist.

1954/1955

Sándor Bortnyik introduced his series entitled Modernized Classics to a small gathering in the faculty room. The exhibition entitled Ten Years of Growth at the Academy of Fine Arts was organized.

1955/1956

A celebration was held in honour of Aurél Bernáth’s 60th birthday. Sándor Bortnyik announced his retirement and recommended Endre Domanovszky as his successor.

1956/1957

In its September session, the Directorial Council decided against public diploma defence presentations. On 15 October, students organized a school assembly with oppositional overtones. On 23 October, a number of students and faculty members participated in anti-Soviet protests. With the participation of students and teachers, the Revolutionary Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts was formed. On 6 November, four Russian soldiers entered the Academy building and shot four students: Zoltán Csűrös, Sándor Komondi, József Kovács, and Antal Bódis. Teaching recommenced on 14 January, with a new pedagogical program. The strict curriculum and academic discipline gave way to a greater freedom of studies. The History of Philosophy was taught again, replacing Marxism. Rehabilitation and Disciplinary Committees were established. General Secretary Károly Bíró and Party Secretary Zoltán Rozsnyai were removed from their positions. László Bencze, Károly Koffán, András Csanády and Róbert Muray were laid off.

STUDENTS IN THE CIRCLES OF THE EUROPEAN SCHOOL

Those young people who began their studies at the Academy in the final year of the war still had hope that the time of a European-oriented modernism that was free of political pressure would finally come. A portion of the students consciously sought to establish connections with the artists of the European Circle, which had been established in the autumn of 1945. The exhibitions held by the Circle (as well as by the Group of Abstract Artists, which was later formed by some of its members) were characterized by the dominant aspirations of post-war European art – by various versions of surrealism, informel, and abstract expressionism. Young, path finding artists established a personal relationship with Endre Bálint early on. They obtained their information about the developments of 20th century modernism by leafing through the albums of Picasso, Braque, and Chagall at the Academy’s library. The majority of the Academy’s faculty, at this point, represented various “shades” of plein air and classicisation, carried over from the period between the two wars. The only alternative to this naturalistic perspective was offered by Jenő Barcsay, who began teaching at the school in 1945, and who represented a direct link to the constructive-surrealist legacy of Szentendre’s art. With his support, in the summer of 1947, students had the opportunity to work in Szentendre. The contemporary art milieu of the town provided an alternative to the stale plein air painting which was part of the official curriculum. During this period, György Hegyi, Ferenc Jánossy, Zoltán Nuridsány and András Rác were all active participants of the Szentendre art scene. “This was a period when, instead of studies conducted at the Academy, we painted abstract paintings” – remembered György Hegyi.

While the abstraction debate was gaining momentum in the art press, young artists who moved within the circles of the European School could experiment within the varied palettes of surrealism and nonfigurative art. Their canvases were teaming with organic landscapes, masked faces and cubist, constructive creatures. In the autumn of 1946 and in January 1948, their works were showcased in the exhibition space of the European School with the title Youth, where, in addition to works by Simon Hantai, paintings by György Hegyi, Ferenc Jánossy and Zoltán Nuridsány were also featured. As articulated by Péter György and Gábor Pataki: this generation “in a free human climate, could have deservedly carried on the legacy of the European School”. While, for a few years after 1949, a number of these young artists (Ferenc Jánossy, Zoltán Nuridsány, Gellért Orosz and Gyula Sugár) continued to exhibit as an independent artist group called “Quadriga”, the turn in art policy that occurred in 1949, however, radically eliminated modernism.

Although in the official curriculum, no space was allotted to abstract, formal experiments, certain “havens” where these could be continued nevertheless existed. In François Gachot’s French classes, aside from studying the language, students could also get a taste of contemporary European mentality. Constructive, decorative design could be practiced in Jenő Barcsay’s Glass Design class, which was also attended by György Hegyi and Gellért Orosz. After Sándor Bortnyik put an end to Barcsay’s workshop in 1948 for engaging in “suspicious formalist experiments”, Géza Fónyi’s Mosaic Design class became the last sanctuary for modernist students. In György Hegyi’s words: “The mosaic class became a real phenomenon at the Academy. Because of its decorative aspirations, it was the only freer alternative, and it seemed to us as the only place where the growing impetus of ‘the modern’ could be salvaged and cultivated. A memory of the Mosaic Design class and the work conducted there is preserved at the main entrance of the Academy building at 71 Andrassy Avenue, where Fónyi and four of his students created a floor mosaic to commemorate the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. In the mosaic of the well-preserved entrance hall, which has just been reopened, the subjects that were taught at the Academy are represented by symbolic objects: Painting (Ferenc Jánossy), Sculpture (Erik Scholz), Art History (Zoltán Nuridsány) and Descriptive Geometry (Géza Fónyi). The crest at the centre was created by Zoltán Csákvári Nagy. In the year of the first public diploma defence, both András Rác and György Hegyi presented figural mosaic compositions.

MASTERS IN CHANGING TIMES

During the period following WWII, the entire teaching staff of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts was, in essence, replaced. During the years of the war, the institution was led by Jenő Bory (1943–1945) and Lajos Varga Nándor (1945). In 1945, László Kandó was elected as rector by the Rector’s Council. He was replaced two years later by sculptor Pál Pátzay (1947–1949), who was also in charge of managing the Art Department of the Ministry of Public Education.

After 1945, faculty members who had been appointed between the wars continued to teach art and theoretical subjects for a few more years. Jenő Bory, sculptor, and Dezső Pilch, teacher of watercolour, had taught at the Academy for the longest time (since 1918). A portion of the faculty in the Painting Department represented various modes of Műcsarnok and plein air naturalism (László Kandó, Rezső Burghardt, István Boldizsár, and Gyula Rudnay), while there were also others who worked in the spirit of neoclassicism and Novecento (Béla Kontuly and István Szőnyi). Between the two wars, sculpting was taught by renowned artists, who also had public art commissions (Zsigmond Kisfaludi Strobl, Ferenc Sidló and János Pásztor). Architecture was taught by Károly Andreetti, Jenő Lechner and Gedeon Gerlóczy, while the lecturer for Art History was Ernő Molnár.

Initially, the employment of new master teachers was guided by practical considerations, including the large number of those about to retire. In the academic year 1948/1949, however, numerous members of the previously established faculty were either laid off or forced into retirement, effective immediately. By 1949, of the long-standing master teachers, only two remained to introduce the new curriculum for the new academic year: István Szőnyi and Zsigmond Kisfaludi Strobl. As of 1949, the year of the turn, until 1956, the Academy was under the leadership of Sándor Bortnyik, who had been appointed director by the Ministry. The post of chief secretary was filled by Károly Bíró, Mátyás Rákosi’s stepbrother. The ideological adherence of the institution to the official standard was safeguarded first and foremost by Russian language teacher (and party secretary) Zoltán Rozsnyai. In the autumn of 1956, Endre Domanovszky assumed directorial duties at the Academy. Between 1947 and 1952, more than forty new faculty members were employed at the school. Aurél Bernáth became the new head of the Painting Faculty, which, during his leadership, included such avantgarde artists of the 1910s as Róbert Berény, Bertalan Pór and János Kmetty. A number of teachers had conducted nonfigurative, surrealist experiments prior to the war (Jenő Gadányi, Gyula Hincz and Géza Fónyi). Gyula Pap studied at the Bauhaus in Weimar during the twenties. Prior to 1948, Béla Bán still had joint exhibitions with members of the European School. A number of faculty members had previously taught in the public colleges: László Bencze at the Huber Dési College, Károly Koffán and András Beck at the Derkovits College. Conservation training, established by Nándor Kapos, was initially part of the Academy’s painting programme.

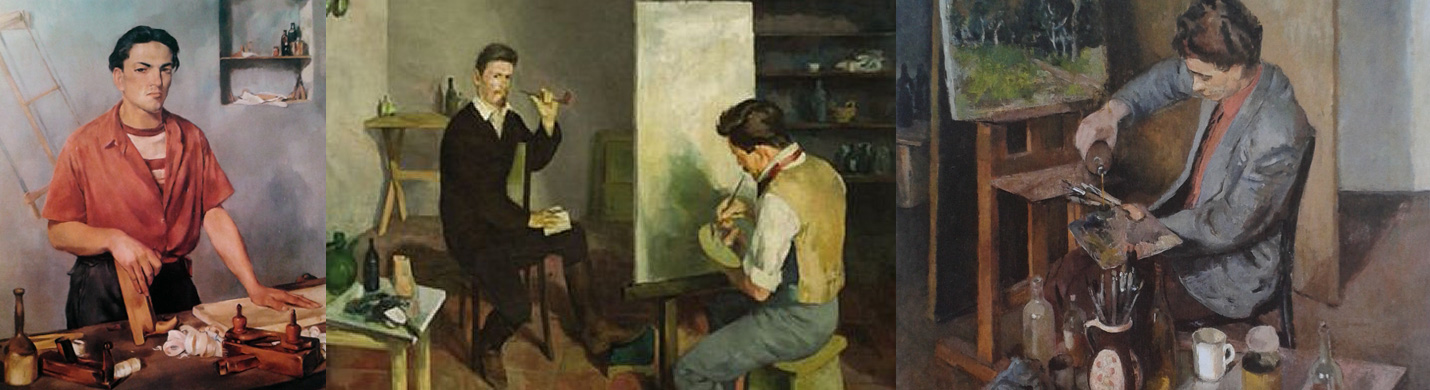

The few works by master teachers that are showcased in the exhibition provide a good illustration of the directions of stylistic path-finding. Teaching and learning, as tools for the ideological re-education of a new generation, was a key topic of the era: Róbert Berény and Endre Domanovszky paintings of life at the Academy are connected to this well-liked theme. (Conservation work for Berény’s painting was performed for the purposes of this exhibition by the professors and students of the Hungarian University of Fine Art work.) Sándor Bortnyik’s series entitled Modernized Classics, which he painted during the early fifties, attests to the paradoxical relationship of the former avantgarde artist to the legacy of modernism. János Kmetty’s slightly cubist life scene and Szőnyi’s protestingly eventless landscape detail, however, are characteristic examples of a “dissolving socialist realism”. Of the master teachers of painting, Aurél Bernáth and István Szőnyi’s relaxed, visualistic painting style was especially influential among students.

In 1945, the newly vacant teaching posts of the Sculpture Department were filled by Béni Ferenczy and Pál Pátzay. Ferenczy, however, was forced into retirement in 1950. Alongside them, András Beck, Iván Szabó, Tamás Gyenes and Sándor Mikus comprised the rest of the Department’s teaching staff. It was also in 1945 that Jenő Barcsay was invited to teach Anatomy. The one-person Graphics Department, till then represented by Nándor Lajos Varga, was expanded to include a number of new teachers, among them Károly Koffán and György Konecsni, who had been asked over from the Academy of Applied Arts. Sándor Ék, with his convincing communist past, was appointed to head the Department.

Pedagogical Methodology was taught by Kálmán Gáborjáni Szabó. As for the History of Architecture, the post, from which Gedeon Gerlóczy was removed in 1949, was occupied at once by Virgil Borbiró (Bierbauer), who, in 1951, was also removed from the Academy. Art History was taught by Béla Újvári and Máriusz Rabinovszky. After Rabinovszky’s death, Lajos Végvári took over. Lectures in Literature and the History of Education and Culture were held by László Cs. Szabó, associated with the second generation of the literary journal Nyugat. Following his immigration to Italy in 1948, these subjects were taken on by János Faludi.

THE ACADEMY IN THE FIFTIES

In the cultural policy of the fifties, educational strategy constituted a field of its own. The gesture of opening was a key feature of higher education reform: the size of the student population was to be increased and its social composition changed. It was from the academic year 1949/1950 that the political turn could definitely be felt within the walls of the Academy. Following Sándor Bortnyik’s appointment as chief director, major changes were introduced in four areas: in addition to altering the admission process along with the structure and content of the teaching material, education as a whole was put under the control of the Ministry of Public Education, thus bringing an end to the Academy’s autonomy.

The change in the social composition of the student body was already apparent in the first year of the reform: 46% of freshly admitted students were of a working class-peasant background. A portion of these students were brought in from the countryside through a talent recruitment program conducted by teachers. As many of these young people hadn’t graduated from high school, a new specialized, one-year crash course was introduced during which, after taking only those subjects that were absolutely necessary for further study, students could obtain their high school diploma. The strikingly different cultural background and degree of preparedness of this new freshmen generation caused considerable problems for the Academy’s master teachers, who aimed for uniformity in studio work. In an attempt to help these students catch up, they were each paired up with a fellow student of a middle class background.

By 1949, the new organizational framework of education took shape as well. The previously elected rector was now replaced by a Ministry-appointed director, who managed the institution together with the Chief Directorial Council, comprised of the heads of the four chief faculties: the General Faculty, which was taken by first and second year students, followed by the Painting, Sculpture or Graphics Faculties. (The Visual Education Faculty was suspended for some time.) Initially, optional faculties included Wall Painting, as well as Glass, Mosaic, and Carpet Design. By 1951, however, in addition to Panel Painting, only Wall Painting and Mosaic Design remained. Conservation training was, at this time, still contained within the framework of the Painting Faculty. Within the Graphics Faculty, students could choose between poster design or printmaking, and within the Sculpture Faculty, they could opt for monumental or small sculpture. Students could no longer freely choose their teachers.

According to the new Organizational and Educational Policy (approved in 1949), the goal of the Academy was to “train skilled artists who place art in the service of building a socialist society. These artist are responsible for creating the new Hungarian fine arts in accordance with the requirements of socialist realism. Hungary’s new fine arts are to be national in form and socialist in content and, in all genres, must provide a true reflection of reality and radiate the optimism of building the socialist system of the Hungarian People’s Republic.” The collective viewing of the Painters of the Soviet Union exhibition at the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest in 1949, along with an offering of portraits honouring Stalin’s birthday, served to strengthen the socialist façade of the Academy’s art education. Students began each day by analyzing the leading articles of Szabad Nép (Free People), the central paper of the Communist Party, and accompanied by their teachers, regularly visited factories. With the aim of fostering a closer relationship with the working class, summer workshops were held in new locations: the industrial centres of Sztálinváros and Tatabánya.

Solidifying work discipline, along with monitoring the content and progress of education, was one of the main pillars of the reform. Teaching took place according to a strict, weekly scheduled structure. Faculty members were expected to adhere to the curriculum and were held personally accountable for any deviations. All exercises were uniform and mandatory for all students. Members of the faculty were responsible for preparing weekly, monthly and semester reports on the work conducted in their classes, which were then submitted to the Ministry. For the bureaucratic system of cultural management, total surveillance and uniformity provided the guarantee that art education had the expected ideological content and was progressing in the appropriate direction. Disciplining and monitoring students also comprised part of this approach: teaching began strictly at 8:00 am, tardy students were held publicly accountable. A “Ten-minute Movement” was initiated in an effort to eliminate incidences of absence and tardiness. The issue of students who were notoriously absent or late for class was discussed at disciplinary hearings, which were frequently held with the objective of penalizing ideological and behavioural transgressions.

While this rigid regulation of the curriculum eased up somewhat following Stalin’s death in 1953, the regular submission of reports and a strictly structured teaching schedule remained mandatory until the reform of 1957.

PUBLIC DIPLOMA DEFENCE PRESENTATIONS

The first public diploma defence presentation at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts was held at the end of the academic year 1950/1951. The purpose behind introducing this new practice was clearly to show the outside world that the Academy had changed directions in terms of both its ideology and politics, on the one hand, and that socialist realism in fine arts was the exclusive path on which higher education in art would proceed. In the words of an art critic writing in the periodical Szabad Művészet (Free Art): “The presented works also attest to the efforts of the Academy’s students and faculty to eliminate any remnants of abstractionism and formalism and to implement the correct manner in which the human being and his activities are to be represented.” In connection to the diploma works of the academic year 1951/1952 – the first defence presentation for which the minutes have been preserved for posterity – Director Sándor Bortnyik laconically concludes: “The diploma works are a means of examination which assesses not only the work of the students, but the teaching faculty as well.”

The presentation of the diploma works was preceded by the preparatory activities of the fifth and final year, during which students worked on their diploma project while maintaining constant consultation with their supervising master teacher. At the defence, in addition to showing their finalized diploma works, students also had to present a summary. An evaluation by the invited jurors followed, to which students could respond. Finally, the Diploma Committee made their decision as to whether the given diploma work was accepted or rejected. The system of considerations according to which the diploma work was judged reflected the aesthetic values of socialist realism. Students were expected to produce art that engaged the “heroic, party-centric, strongly construction-oriented” themes of reality and captured “typical characters” and “typical circumstances”. Furthermore, these works were to clearly express and elaborate on contents carrying the socialist ideal and were, in all cases, to be carried to completion. The diploma defence presentations were also covered by the press, providing the public with detailed analyses of the defended works.

In preparing for the exhibition, we discovered an album that contained the photographs of diploma works from the academic years 1950/1951, 1951/1952, 1952/1953 and 1953/1954. Based on this material and on the preserved minutes of the presentations that took place between 1951 and 1954, it is possible to reconstruct the Academy’s diploma defence events from this period. While the majority of degree works consisted of paintings and sculptures, in connection to other courses within the curriculum, posters, book illustrations, mosaic works and conservation documents were also included.

The diploma works offer a good illustration of the keenness of students (and their teachers) to conform to the thematic and stylistic expectations of the socialist realist norm. A strikingly large number of works focus on the theme of studying (Lajos Szabó: Physics Experiments with Worker Students, 1951; Iván Masznyik: Studying in Pairs, 1951; András Wrobel: Teaching the Illiterate, 1952). Many compositions are set in ateliers and focus on art and the process of its creation (Lajos Újváry: Master Szőnyi Makes Some Corrections, 1951; József Littkei: Industry Students Visiting a Sculpture Atelier, 1951; József Kórusz: Visitors at the Munkácsy Exhibition, 1953). The works often illustrate such socialist realist movement-related activities as working on the bulletin board, signing so called peace loans, holding illegal seminars, and conducting peace talks. Sculptors sought to carve out the new heroes of socialist ideology, lending heroic statures to the figures of iron foundry workers, electricians, youth workers, miners and cotton picking girls. A modicum of loosening to this restrictive visual scheme was detectible (in parallel to political easement) as of the academic year 1953/1954. At this point, there was a discernable decrease in the number of politically-committed works, giving way to themes and life scenes of a more neutral tone. (Ferenc Hock: Home Concert, 1954; Katalin Szilveszter: Still Life with Sculpture, 1954; László Óvári: Picnic, 1954).

The exhibition features a number of works that constituted the “main attractions” of these diploma defence presentations. These include paintings by Ignác Kokas and Györgyné Kádár, charcoal sketches for the diploma works of Tamás Konok and Tibor Csernus, graphic series by András Csanády and Béla Kondor, and a sculpture by István Kiss.

THE AESTHETICS OF A NEW ACADEMISM

Following the 1949 turn, education at the Academy – following in the footsteps of the Moscow Academy of Art – returned to the methods of 19th century academies. The plaster models, which had more or less been neglected in the naturalistically oriented education of the early 20th century, became important teaching aids once again. General training began with copying antique-renaissance plaster models (the head of Michelangelo’s David, anatomical sculptures, and reliefs), followed by studies of life drawing. In-depth anatomical studies conducted according to Jenő Barcsay’s method also constituted an important element of the mandatory curriculum. In 1950, naturalistic image making as a direction was still a solid dogma of the curriculum: “The most important subject in drawing, painting and sculpture is the human being (the human body, motion, movements of the body at work). In painting, an exhaustive, precise study and depiction of other real and natural phenomena (including still life, landscape, animals, interiors) is an additional requirement.”

Precise drawing formed the basis of the Soviet scheme of academic classicism. Drawing, as a tool of rational, accurate observation, signified a kind of moral insurance in the face of the unstable, individualistic “temptations” posed by painterliness. “A stronger, more solid competence in drawing helps curb tendencies toward sketchy, imprecise ‘painterliness’”, stated Sándor Bortnyik in his 1952 report. For this reason, in their first two years, students spent most of their studio time drawing. In the interest of disciplined graphic articulation, students primarily used graphite pencils. In contrast to the impulsivity of charcoal, this better facilitated the dry and objective mode of expression that was preferred. The remaining pillars of this new academism were completeness and remaining “true to the material”. The aforementioned curriculum had this to say on the matter: “All artworks and studies must be completed, ensuring the trueness of the representation to the subject material (skin, hair, foliage, etc.) and depiction of texture.” These expectations also pertained to colouring and brushwork.

These means served the production of complex, ideologically thought-through compositions. (The artwork was often referred to as a “work piece” in an effort to better emphasize its practical purpose.) As of their third year, students chose their faculties and continued their training in paintings or sculpture, with the conclusion of creating a multi-figured composition as the crowning achievement. The curriculum laid down the expectations regarding this final projects as follows: “The key subject of compositions is the study and depiction of the reality of our People’s Democratic Republic, the relationship of the labouring people to their work, the portraits of our leaders, their acts and their relationship to the people.” During their compositional studies, students were to ensure clear visual arrangements, the authentic psychological representation of their subjects, and easy interpretability of the depicted scene. The aesthetic alternative to the socialist realist perspective was primarily represented by István Szőnyi and Aurél Bernáth, who were criticized for their light-shadow and colour based compositions, as well as setting poses for models as “an end in itself”, neglecting predetermined thematics, and focusing on painterly, colour-centred problems rather than the importance of completing the artwork.

FROM SHADOW INTO LIGHT

GRAPHIC ART EDUCATION IN THE FIFTIES

During this historical era, a sense of relative freedom characterized the work of the Graphics Department, which allowed for experimentation on the part of students in an effort to find unique alternatives to officially sanctioned art. In 1948, as Nándor Lajos Varga’s successor (and former student), Károly Koffán took charge of the department. Koffán’s connection to the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts went back further in time, however: In 1940, the prints of his album containing wood and lino cuts, entitled De profundus, were made here. François Gacho, the Academy’s French teacher with an in-depth awareness and understanding of the contemporary art scene, wrote the introduction to the volume. Koffán also gained recognition as an art pedagogue. The approach with which he taught at his drawing school in Erzsébet Square was grounded in the principles of printmaking. When, in 1948, he was invited to teach at the Academy, in his person, an artist who was open both in terms of style and technique was added to the teaching faculty of the department.

In previous times, printmaking had been an option open to painting and sculpting students, giving them a means to acquire skills and competence in the field of graphic art (which also helped in making a living later on). As a result of the 1949 reforms, it became a faculty of its own, which students could opt for after their first two years of general art studies. Sándor Ék, György Kádár and György Konecsni were newly hired to teach at the Academy. Konecsni was called over from the Academy of Applied Arts by Sándor Bortnyik, with the intention of strengthening the applied aspect of the printmaking programme. Bortnyik, who, prior to the war, had been internationally known as a modern poster artist, was keen to include – in addition to graphic art, placed in service of autonomous image making – the applied branches of graphics in the faculty’s repertoire. Thus, in the academic year 1950/1951, students also had a chance to try themselves at poster, wrapping paper and stamp design. Students studying autonomous image creation in printmaking – which had by now become a faculty of its own within the chief faculty – had an opportunity to familiarize themselves with various printmaking techniques and book illustration design.

Sándort Ék was appointed head of chief faculty, who, in turn, asked György Konecsni to head the Faculty of Applied Graphics and Károly Koffán to be in charge of the Faculty of Graphic Art (Printmaking). Koffán created an inspiring and experimental atmosphere for his students. The symbolic figures in his own drawings – always reaching from darkness toward light – along with his “tenebristic” perspective, offered students a refreshing alternative to the languidly genial painterliness of official art. Although, once he began teaching, he suspended his activities as an artist (and turned his attention more toward ornithology), it was precisely this passivity through which he was able to express his critique of the system. Many of his students employed his flashing, black and white contrasts in their own work. The diploma work of his student and later teaching assistant, András Csanády, also utilized this understated yet dramatic element of his art. Koffán’s technical experiments with copper engraving were given new form in Béla Kondor’s novelty-like, grotesque historicism. Kondor’s trendsetting artistic vein and sense for the tragic in his poetic imagination pushed the limits of the dry realism of the socialist realist paradigm. Koffán’s Graphic Art Department offered Kondor a safe haven and inspirational artistic atmosphere. His diploma work entitled Dózsa Cycle, which he defended in the summer of 1956, gave testament to the visual style of the new generation in all its richness – a tragic tale full of grotesque pathos, resigned irony and visionary historicism with reference to the resurrection and fall of our heroes. To contemporaries looking back on this period with the hindsight of the Revolution, this period gave form, with almost prophetic power, to the rising and falling heroes who fought for freedom. In parallel to this, a tone different from the tragic pathos of official historical representation was also emerging in Arnold Gross’ drawings, whose fairytale-like scenes were peopled with ironic and grotesque heroes.

1956

IMAGES OF REMEMBERING

Numerous students and teachers participated in the events of the 1956 Revolution. This exhibition features a selection of works that offer insight into the experiences and memories of eye witnesses to these events, as articulated in image form. Few works of art were created during the chaotic days of revolutionary upheaval, and even less have been preserved for posterity. Róbert Muray’s photo series, for instance, was lost or destroyed. (Because of his photos, which were published in the western press, the artist was dragged through the mud and removed from his teacher’s assistant post.) Béla Gönczi’s photo series shot in the neighbourhood of Corvin Lane on 28 October 1956, however, has – luckily – survived. The horrors that people lived through during those days – fusillading, executions, and lynchings – appear in the paintings of a number of artists. These young men captured what they witnessed – András Baranyay saw the victims of fusillading at Kossuth Square, János Major (still a high school student) saw the body of a lynched man in Köztársaság Square, and Imre Kocsis witnessed the death of a friend – by painting it. István Szőnyi composed a drawing with the figures of the bereaved and those carrying the dead. In these works, Szőnyi returned to the abstract, pathos-driven style of his neo-classicistic copper engravings created during World War I. Instead of focusing on concrete political events, his drawings pay tribute in everlasting form to the universal human drama of bereavement and burial. Similarly to Szőnyi, Baranyay and Ambrus also depicted their subjects in an exalted, pathos-strewn style of drawing. In Sándor Tóth’s destroyed sculpture The Standard-bearer, and his linocut series offered in memoriam to his fellow student Zoltán Csűrös murdered by Russian soldiers, an allegorical visual representation returns, which elevates these events into the realm of the universal. Similarly, Imre Veszprémi’s sculpture of a bereaved figure and his drawings which refer back to Goya’s series The Disasters of War were all attempts at finding a symbolic mode of visual expression for all that took place. Gábor Pásztor’s lithography was only created later with the intention of summarizing the events of the uprising. (The print was supposed to be part of a graphics album commemorating the Revolution, which was never actually published by Képcsarnok Vállalat (“Gallery Company”).

For our exhibition, we aimed to select works that date back to the events of the 1956 Revolution, whose authors had direct links to the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. It goes without saying that such works exist in larger numbers than what is included in our presentation. A number of related works are also featured at parallel exhibitions commemorating the events of 1956 (including paintings by Ernő Dede, Oszkár Papp, and Zoltán Csizmadia).

In the other part of our exhibition, we wished to invoke the faces of those who were there: students, teachers, revolutionaries and victims. Of these works, the large-scale self-portraits of Sándor Komondy, who died as a young man at the age of twenty-five, are especially of interest, attesting to his stubborn attempts at self-analysis. Through his paintings, we may catch a glimpse at the characteristic features of a generation that was robbed – by an era of historical events, wars, revolutions, persecution and suppression – of its chance at self-actualization and artistic self-exploration.

The event is supported by the Memorial Committee established on the 60th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.